Riding the big grand-daddy to Beijing

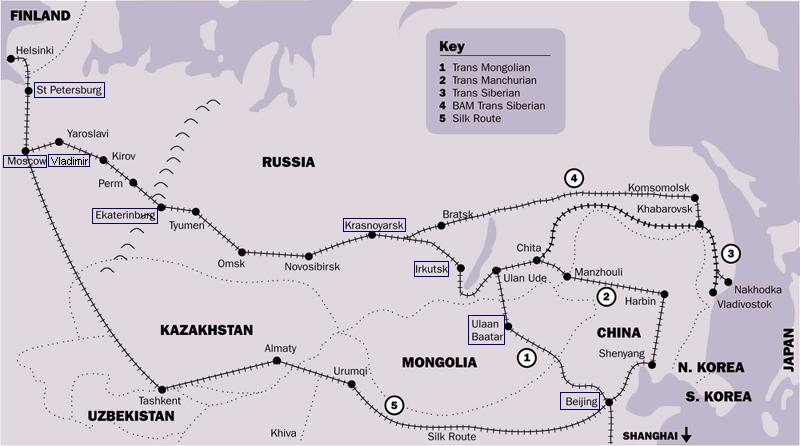

The Trans-Siberian railway is the big grand-daddy of train trips. The train from Moscow to Beijing covers 7621 kilometres and takes six days. If you continue straight through to Vladivostok that's an extra couple of thousand kilometres. As a guidebook points out, once you've done the Trans-Siberian every other train trip is "once around the block with Thomas the Tank Engine". This trip has loomed large in my imagination for years, and it was a huge thrill to find myself on the platform at Kursk station in Moscow, waiting to board the first leg of my Trans-Siberian adventure.

The Trans-Siberian proper is the Number 2 train (the 'Rossiya') from Moscow to Vladivostok. Few Westerners take this route because of Vladivostok's remote locale and the difficulty of moving on from there. E and I are taking the more travelled route, 'the Trans-Mongolian', which passes through Mongolia and terminates in Beijing. Having said that, these are working trains and the likelihood of us bumping into other foreigners on the train is quite small. On our 34 hour trip from Yekaterinburg to Krasnoyarsk (our current location) we met three other tourists, but the rest of the carraige was a motley crue of babushkas, Russian soliders on their way to postings and Russian families moving house. The train attracts a wide variety of people simply because it is the cheapest and most efficient form of transport in Russia.

The story of the construction of the Trans-Siberian railway is as monumental as the mythology that has since been built around it. It took 25 years for the first line of track to be built, with it being completed finally in 1916 at a cost of 1000 million rubles. Most of it was built by men wielding nothing more than wooden shovels. The workers, most of them far from home, endured long, cold winters as well as summers that brought outbreaks of plague, cholera and other diseases. But this first line of track was built on the cheap, and there were frequent delays and derailments. Sometimes the train went so slowly that passengers got out to pick flowers and walked along beside it. Following the Revolution, Lenin remarked that "When the trains stop, that will be the end", and the trains continued to run through the Civil War. Later the Soviet Union undertook the repair of the Trans-Siberian line, a huge project which was largely built on the backs of prisoners in labour camps.

The modern traveller, however, need not concern themselves with the suffering behind this remarkable engineering feat. Three legs in, E and I agree: it is a tremendously comfortable ride. In 2nd class, there are four berths in each compartment and nine compartments in each carriage. The provodnitsa (conductor) is the lord of the manor. She (they are invariably women) decides when the toilets are open, when the carriage gets cleaned, and oversees provision of the samovar of boiling water at the end of the carriage. She can also decide to deprive passengers of these things - it is best to stay on the provodnitsa's good side. All except one of our provodnitsas so far have been lovely and extremely hard-working - although we have small Australian-themed gifts in our backpacks should the need arise to sweet talk a surly conductor. Time passes pleasantly on the train. After we store our bags away and sort out our bedding, we make ourselves a cup of tea and gaze out the window at the landscape. This may take up two or three hours of our time, depending on the mood. Then we might reach for a book (E, Solzhenitsyn and me, far less highbrow, Robert Harris's thriller 'Archangel') and read till we're hungry. Then it's time for lunch. We might spend a bit more time over our black bread and salami because we know that we have nothing important or pressing to do for the next day or even next two days. The landscape seems to reflect this mood back at us. There are spots of striking beauty, particularly at this time of year when some trees are ablaze in the reds, oranges and yellows of autumn, but for the most part we are gazing out at clusters of yellow trees or vast stretches of grassland (the steppes). This goes on for hours. The landscape is in no hurry to change, to do anything new or different, and neither are we.

Time passes pleasantly on the train. After we store our bags away and sort out our bedding, we make ourselves a cup of tea and gaze out the window at the landscape. This may take up two or three hours of our time, depending on the mood. Then we might reach for a book (E, Solzhenitsyn and me, far less highbrow, Robert Harris's thriller 'Archangel') and read till we're hungry. Then it's time for lunch. We might spend a bit more time over our black bread and salami because we know that we have nothing important or pressing to do for the next day or even next two days. The landscape seems to reflect this mood back at us. There are spots of striking beauty, particularly at this time of year when some trees are ablaze in the reds, oranges and yellows of autumn, but for the most part we are gazing out at clusters of yellow trees or vast stretches of grassland (the steppes). This goes on for hours. The landscape is in no hurry to change, to do anything new or different, and neither are we.

The train passes through dozens of towns, giving us the opportunity to get little snapshot glimpses into their histories. We passed through the village where the world's first astronaut, Yuri Gagarin, perished in a plane crash; our guidebook warned off stopping in another town for its history of stockpiling dangerous chemicals; and we stopped off in Yekaterinburg, site of the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family and home town of Boris Yeltsin. Being on the train has helped me appreciate just how immense this country is, how many stories there are, and how little I can hope to comprehend on a 30-day visa. But, as I had hoped, it is a thrill to see the country unfold before me on this magnificent train as it rolls on gently towards Beijing.

A few more shots from the train

1 Comments:

Great write-ups...interesting commentary! My family found your blog enjoyable as well...I hope you have as much fun going east as I did west...

trans-eurasia.netscene.org

Post a Comment

<< Home